“Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.” If you have listened to an investment advisor for a minimum of 10 minutes, you are probably familiar with this statement. It has become a truism that diversification is essential to any sound portfolio management.

Is that not the conclusion of Harry Markowitz’s popular 1952 article (Portfolio Selection) and the Modern Portfolio Theory it birthed?

Yet, many investors insist that concentration is the way to go. “Going big on a few bets is the way you make money in the market,” they insist.

Is that not what Warren Buffett was affirming when he said, “Diversification is protection against ignorance. It makes little sense if you know what you are doing.” “Opportunities come infrequently,” he also said. “When it rains gold, put out the bucket, not the thimble.”

So, which is it: Reducing portfolio risk with diversification or maximizing opportunities (and returns) with concentration? Asked differently, is diversification the provenance of those navigating the stock market maze without a compass or the smart effort to ensure that there will be an egg to eat even on bad days?

We’ll seek to answer this question in this article.

The case for concentration

Higher returns

The primary argument for portfolio concentration is that it provides higher returns and helps build wealth faster.

“Investment portfolios that obtain the highest returns for investors are not usually widely diversified,” according to Investopedia. “Those with investments concentrated in a few companies or industries are better at building vast wealth.”

They include William O’Neil, Jesse Livermore, and Gerald Loeb as examples of those who have taken this approach.

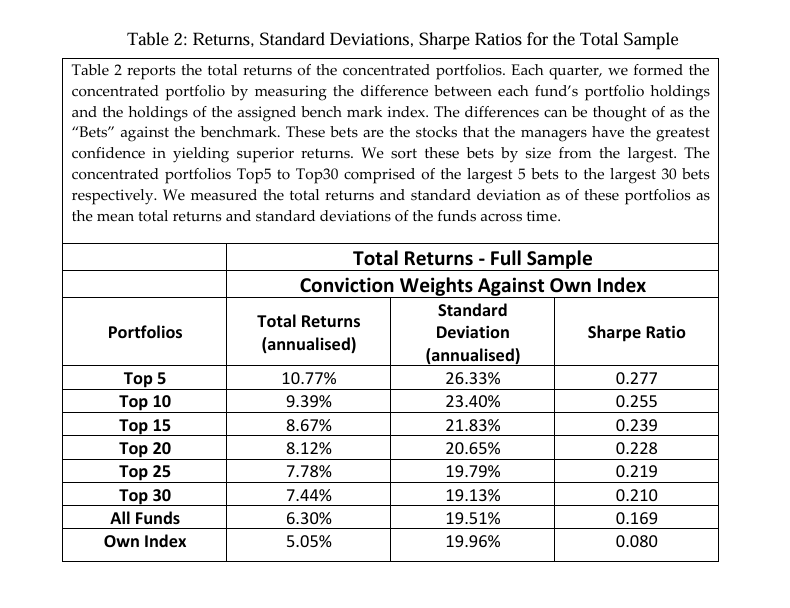

In a study of 4,723 actively managed mutual funds in the US using data between 1990 and 2009, researchers writing for The Paul Woolley Centre for the Study of Capital Market Dysfunctionality found that concentrated portfolios outperformed diversified portfolios.

Performance of concentrated and diversified portfolios between 1990 and 2009

Source: University of Technology Sydney

The researchers constructed the concentrated portfolios by comparing a mutual fund to its index and identifying holdings in the fund that are not in the index. They considered these holdings as the fund managers’ bets (since they were not required by the index) and created a portfolio of the top 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 bets (sorted by size).

“The more concentrated the portfolio, the better the performance, as we see a progressive decrease in realised returns as the concentrated portfolios are expanded from five stocks to 30 stocks,” they commented.

Furthermore, between 2010 and 2023, the top 10 performers of the S&P 500 Index outperformed the top 10 contributors to the index, according to a study by Gresham Partners.

Top 10 Performers of the S&P 500 Index Vs Top 10 Contributors, 2010-2023

Source: Gresham Partners

“This reiterates that, if executed proficiently, there are abundant opportunities to surpass the return of the index itself,” they concluded. In other words, a strategy that focuses on picking the best stocks is superior to one that mainly tracks the index.

Beating the market

Furthermore, concentration is the only way for mutual funds to justify their existence, since they need to beat the market (by a margin higher than the difference between their expense ratios and that of passive funds) to make them more appealing than passive investing.

On the other hand, a diversified strategy will mean mutual funds replicating the returns of indices while charging higher fees than passive funds. Where then is the appeal for investors to embrace active management? No wonder Brett Robertson, president of Richmont Investment Management, insists that diversification is a recipe for mediocrity.

More focused research efforts

A fund manager who has to keep a tab on 30 stocks may not give each stock the attention it deserves compared to one who has to manage only ten.

“I didn’t make a conscious decision in 1987 to run concentrated portfolios,” said John Fisher, the CEO of Wilson/Bennett Capital Management. “The analytical process — valuing businesses and pieces of businesses — lends itself to a concentrated approach. We get to know the companies well, and if you’re following 12 or 13 stocks, it’s much easier to know what’s going on in the underlying businesses.”

In other words, with fewer stocks, it is easier to conduct the kind of thorough analysis involved in proper stock selection (buying and selling) that a Benjamin Graham or Warren Buffett will approve.

Riding with the best

In Only the Best Will Do, Peter Seilern, founder of Seilern Investment Management, presents a case for buying only exceptional businesses that have durable competitive advantages. “Constructing a portfolio of what he calls quality growth stocks is the only true way to minimise the risk of losses while simultaneously maintaining a high probability of above average long-term returns,” said Jonathan Davis, an investment expert, in the foreword to the book.

This idea of focusing on only the best companies is easier to implement with portfolio concentration than diversification. “If one manager holds 40 stocks, you might get his 10 best ideas, while the other 30 are filler,” said Greg Horne, president of Ashbridge Investment Management. “I would just as soon get the filet.”

In essence, mutual funds that use portfolio diversification will have to include some stocks because they are part of a given index, not because they are part of “the best.”

The case against concentration

Failure of active funds to outperform the market

While arguing for the benefits of portfolio concentration, Lauren Rublin, senior managing editor at Barron’s, a financial magazine, admitted: “Screening Morningstar’s Principia Plus database turned up only three mutual funds with 25 or fewer stocks that beat the S&P 500 over three- and five-year periods.”

Advocates of passive investing and diversification have pressed this wound of portfolio concentration over the years. Of course, one can point to some outstanding funds that have outperformed, but the average investor should be more interested in average performance over the long term.

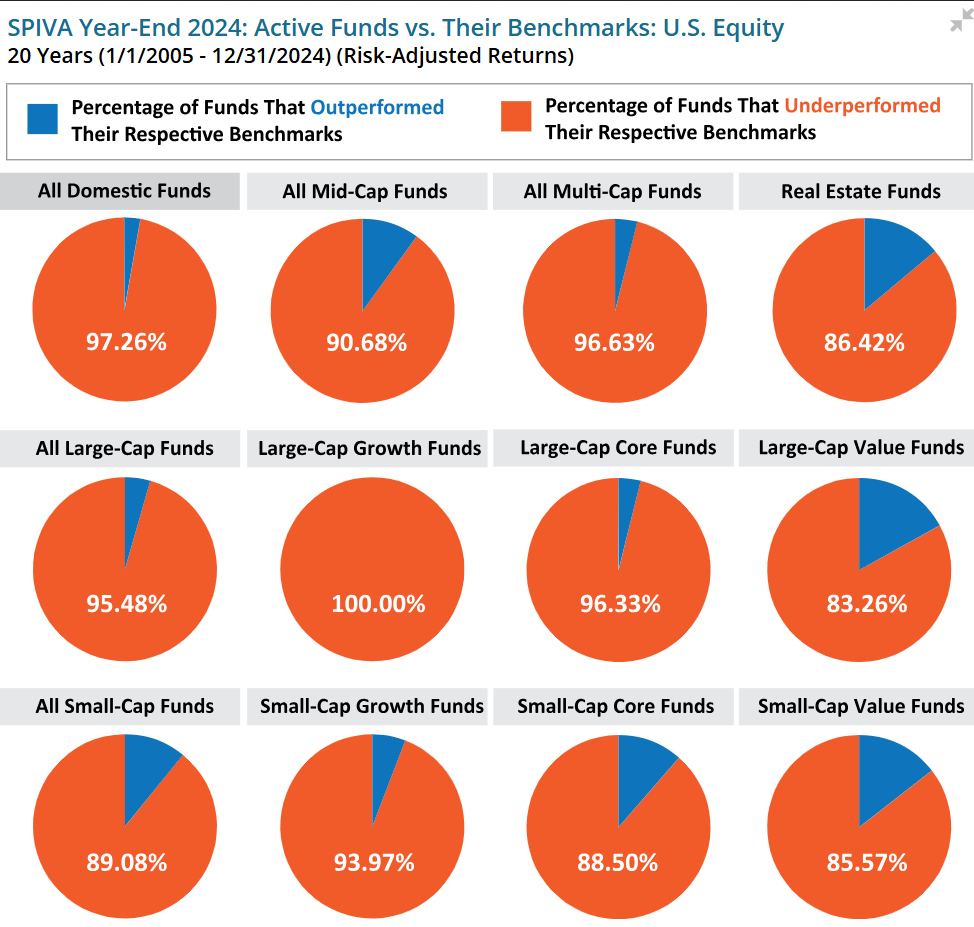

“A lack of consistency by active fund managers in outperforming their respective indexes has been a constant theme of S&P Global’s SPIVA U.S. Scorecard,” according to Index Fund Advisors.

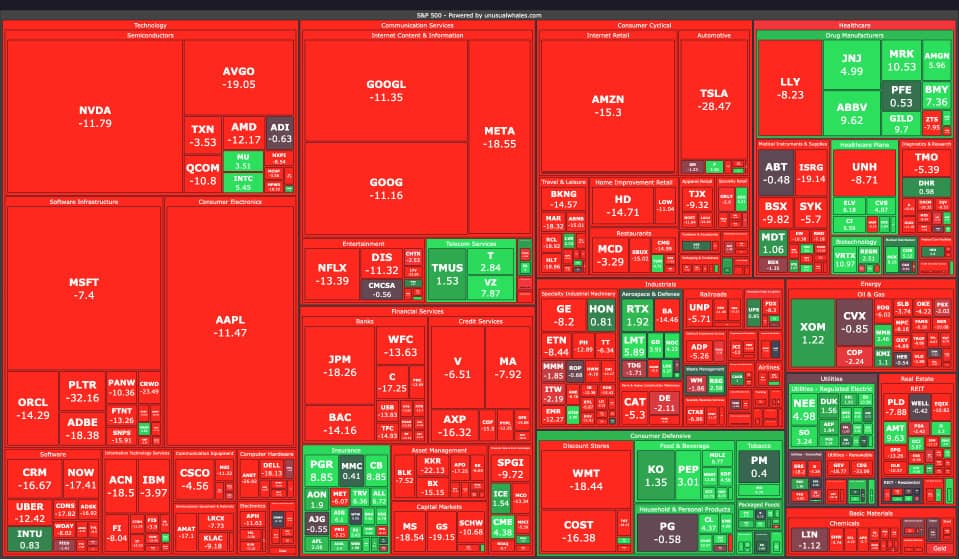

The latest installment of the SPIVA year-end report showed that 97.26% of equity funds underperformed their benchmarks over the 20 years ending 31st December 2024.

Performance of actively managed funds against their benchmarks, Jan 2005 to Dec 2025

Source: Index Fund Advisors

If beating the market is the point of portfolio concentration in active management, then this consistent underperformance by most of the actively managed funds remains its main weakness.

Higher risk

Portfolio concentration requires that you are very good at picking the best stocks. But is it not always possible that there will be one pick that turned out to be the wrong one?

Rublin grants this point: Portfolio concentration is riskier if you define risk as volatility and measure it by standard deviation.

However, many advocates of portfolio concentration will disagree with this CAPM-inspired definition of risk. “As soon as some people see higher volatility numbers in their portfolios, their minds shut down and they see risk,” said Robertson. “To me, if 20 years from now you haven’t met your investment goal, that is the real risk.”

In other words, the true investment risk is failure to achieve your investment goals. Since he believes the higher returns of portfolio concentration make it more likely that you would achieve those goals, he will consider it less risky.

This is in line with Seliern’s argument that the true measure of risk is the permanent loss of capital. Like Robertson, he also sees concentration as the superior approach since it minimizes the risk of a permanent capital loss. “When thinking about risk, it is far more important for the investor to be protected against losing money irrevocably than it is to worry whether the price of what he owns is up or down from one day to the next,” he said.

For long-term investors, then, portfolio concentration is the less risky approach.

The case for diversification

Higher long-term returns

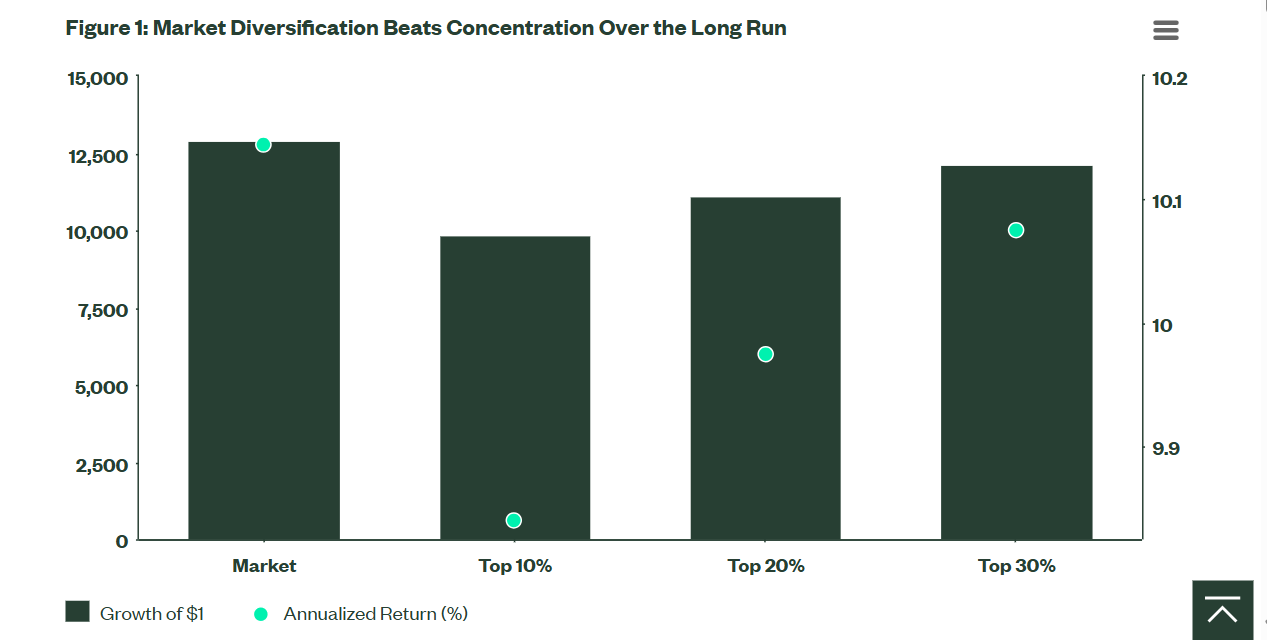

Diversified portfolios produce higher long-term returns, according to a study by Matthew Bartolini, Head of SPDR Americas Research.

As the chart below shows, the market’s annual average return (10.14%) is higher than that of all three concentrated portfolios. Interestingly, the more concentrated the portfolio, the lower the average annual return.

Annualized average annual return of a market portfolio vs 3 concentrated portfolios

Source: State Street Global Advisors

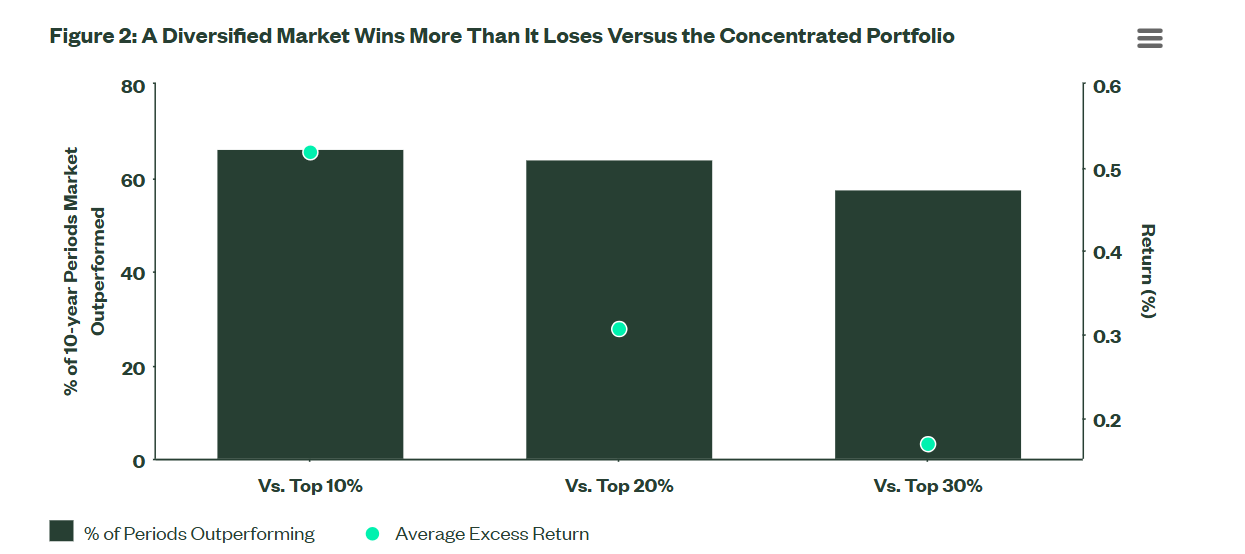

Similarly, using 10-year rolling returns data, Bartolini found that the market outperforms the most concentrated portfolio (top 10%) 66% of the time with an average annual excess return of 0.52%.

10-year rolling annual returns of a market portfolio vs 3 concentrated portfolios

Source: State Street Global Advisors

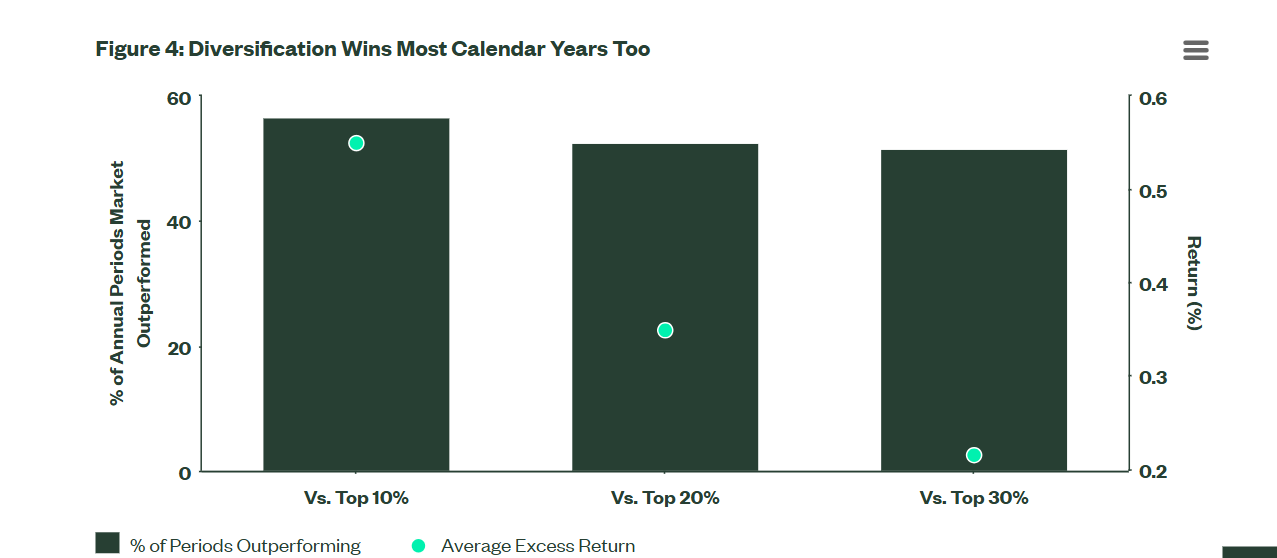

Furthermore, on an annual basis, the market has outperformed all the concentrated portfolios more than half of the time.

Annual returns of a market portfolio vs 3 concentrated portfolios

Source: State Street Global Advisors

Lower risk

Most advocates of diversification focus on how it can reduce the overall risk of a portfolio.

“Diversifying may help reduce how much risk you take on for a level of potential return,” according to Fidelity Investments. “If you’re well diversified, then any problem that affects a specific company, or even an entire industry, may have a more limited impact on your portfolio—because no single investment accounts for a disproportionate part of your money.”

Even advocates of concentration grant that diversification reduces risk, but that is only if we define risk as volatility (measured by standard deviation), which is how Markowitz and William Sharpe define it.

Academic studies of both the US and Chinese stock markets have reached the same conclusion: diversification reduces risk.

The case against diversification

No free lunch

Though diversification reduces risk, that comes at the cost of lower returns, according to Dirk Baur, a lecturer at the University of Western Australia. The only scenario where diversification does not involve a trade-off is if investors cannot know or do not know the risk and return of stocks and just pick them randomly.

However, the study by SSGA above shows that a diversified portfolio can perform better than a concentrated one.

Interestingly, advocates of diversified portfolios don’t insist on this point. They agree that it could underperform or outperform, but that the benefit lies in the stability of returns. “By spreading investments across a wide array of assets, investors can achieve a balance that reduces risk and enhances the potential for stable returns, truly making it the only free lunch in investing,” said Neil Rossiter, managing director of Blackdown Financial, a financial advisory firm.

Transaction costs and management complexity

Individual and professional investors building a diversified portfolio have to carry out more transactions (including portfolio rebalancing), which means higher transaction costs.

Also, managing a portfolio of 40 assets will always be more complicated than a portfolio of ten assets. Furthermore, each asset will not receive the attention it demands and investors may end up following the crowd or their intuition instead of doing quality research..

However, this disadvantage mainly applies to active investors. Passive investors who purchase index funds or ETFs are not likely to incur more transaction costs than an active investor with a concentrated portfolio. Similarly, managing a portfolio of a few ETFs or index funds is not intrinsically more complicated than overseeing a portfolio of a few stocks.

Charting a middle road between diversification and concentration

Avoiding over diversification

Gresham Partners has surveyed various attempts to arrive at an ideal number of securities that should be in a portfolio.

John Evans and Stephen Archer suggested 15 stocks in their 1968 research paper; Burton Malkiel proposed 20 stocks in his bestseller A Random Walk Down Wall Street; Hicham Benjelloun, in a 2010 research paper reviewing Evans and Archer’s initial study, suggested that 40 stocks would provide full diversification and noted that many academics think the figure is 50.

Once a portfolio has this number of stocks, “the plateau of risk reduction is reached.” Said differently, adding more assets to it after this point will not significantly reduce risk.

One implication of this is that even if diversification is beneficial, there is no point going on and on with it as if more diversification always translates to greater portfolio efficiency.

Combining concentration and diversification

Rublin has suggested that “timid souls” who can’t stomach the higher risk of concentrated portfolios can blend concentrated and indexed assets.

Gresham Partners has a strategy similar to this. They build clients’ portfolios using a “core and satellite framework.” The core of the portfolio “might be a low-cost passively managed index fund or, better still, a tax-managed index-tracking strategy where the underlying portfolios are lower-fee, widely diversified, and highly liquid.”

However, the satellite part of the portfolio focuses on generating alpha through a concentrated strategy. “Gresham’s reputation for generating long-term performance rests on our ability to identify strategies across the global capital markets where active management is best suited for driving excess returns, and in turn identifying the best managers to implement those strategies,” they explain. “For these so-called alpha satellites, we must embrace concentration to generate better-than-benchmark performance.”

Another approach is to use the principle of diversification to combine various concentrated portfolios. “When you combine several concentrated portfolios using noncorrelated strategies, you have the best chance of beating a benchmark,” according to Horne.

Rublin explains how the Masters Select Equity Fund implemented this strategy:

“They’ve parceled out assets to six distinguished managers with distinct investment styles, and have charged each — Shelby Davis, Spiros Segalas, O. Mason Hawkins, Richard Weiss, Foster Friess, and Jean-Marie Eveillard — with buying no fewer than five, and no more than 15, favorite stocks.”

The impact of expertise and availability

There is no denying the fact that a concentrated strategy is not for everyone. Its success boils down to the knowledge, expertise, and emotional discipline of the investor or fund manager, as the case may be.

“Sharply limiting the number of holdings in a portfolio does not, in itself, provide any performance edge,” according to Rublin. “It’s the manager who makes all the difference.”

Consequently, retail investors who don’t have the time or expertise to conduct thorough research or the emotional discipline to navigate the short-term fluctuation of a concentrated portfolio may be better off with a diversified and passive approach.

Alternatively, they can invest in several mutual funds that execute a concentrated strategy, mimicking the pattern used by the Masters Select Equity Fund, or choose a single mutual fund that has consistently delivered alpha for its clients.

Conclusion

There is no straightforward resolution to the diversification or concentration debate. Both strategies have arguments for and against them.

However, we have seen investors and fund managers combine both, suggesting that a radical discontinuity may not be necessary. Also, studies showing there is a plateau to the risk-reducing benefit of diversification have helped to chart a middle road between both strategies.

In the end, which strategy to choose (assuming you are interested in only one of them) or prioritize (if you prefer a combination of both) will depend on your risk-return profile.

“Diversification may preserve wealth, but concentration builds wealth,” said Warren Buffett. This is in line with a general belief that the former reduces risk but sacrifices return, while the latter increases return but may increase risk.

However, as we have seen, some studies show that a diversified strategy can be more profitable than a concentrated one. Also, concentration can only be considered riskier if risk is defined as standard deviation rather than a permanent loss of capital.

Though this caveat is important, it is still generally right that more conservative investors should stick with diversification while more aggressive investors should embrace concentration either by picking stocks themselves or investing in mutual funds that do.

0 Comments